|

What limits carnivore recovery in altered landscapes?

|

Expanding human impacts have precipitated the decline of many species, and small populations face increasing uncertainty as global change intensifies in the Anthropocene. Identifying the mechanisms limiting rare or endangered species is critical to developing and assessing conservation strategies that maintain the viability of at risk populations. I work with state, federal, and tribal agencies to address these questions and develop solutions for complex natural resource problems.

Non-invasive hair snare used to assess recovery and reproduction in reintroduced American martens.

Non-invasive hair snare used to assess recovery and reproduction in reintroduced American martens.

From 2012-2018, I worked with the Wisconsin DNR, the US Forest Service, and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission to identify the mechanisms inhibiting the recovery of American martens (Martes americana) reintroduced to Wisconsin. Through a collaborative, long-term research program we used scat and stable isotope analyses to determine marten diets and reveal the limited availability of small mammal prey (Carlson et al. 2014). I then coupled occupancy models with snow track surveys and stable isotope analyses to show that historical land-use change precipitated widespread spatial, temporal, and dietary overlap between martens and competing fishers (Pekania pennanti; Manlick et al. 2017). Lastly, we used a 3-year genetic mark-recapture program to estimate marten abundance, quantify reproduction by translocated individuals, and to parameterize a stage-based matrix model to identify demographic limitations to recovery (Manlick et al. 2017). Collectively, this research found that juvenile recruitment was the proximate mechanism inhibiting population growth, and we determined that prey base and competition ultimately limited marten recruitment. To test the efficacy of ongoing management, I developed population viability analyses and showed that augmentation, a presumed catalyst of population growth, is not an effective strategy for long-term carnivore conservation (Manlick et al. 2017). Many species face similar challenges as climate and land-use change intensify, and this work shows that long-term, collaborative research is key to generating a mechanistic understanding of population dynamics and developing management solutions.

Camera trap detections of martens and fishers in Voyageurs National Park.

Photos: Steve Windels.

Camera trap detections of martens and fishers in Voyageurs National Park.

Photos: Steve Windels.

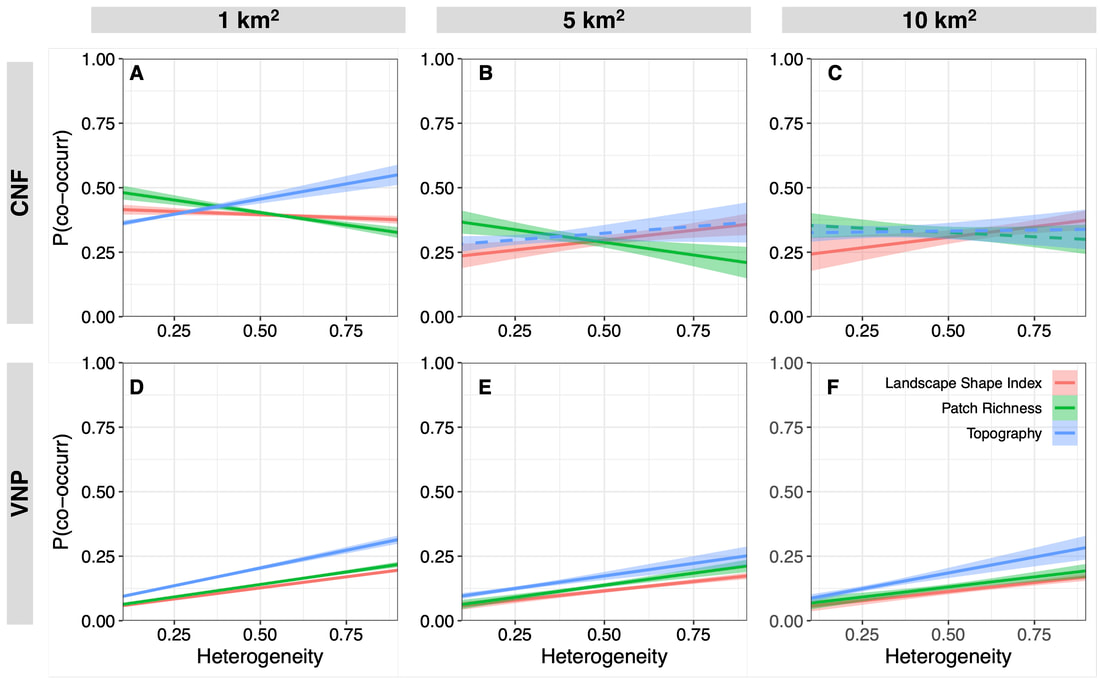

After uncovering extensive niche overlap between American martens and fishers in Wisconsin, we hypothesized that widespread land-use change was limiting niche partitioning and increasing competition (Manlick et al. 2017). Landscape heterogeneity can mediate coexistence among competitors, but increasing human impacts are rapidly homogenizing ecosystems. To test the relationship between landscape heterogeneity, niche overlap, and species coexistence, I compared marten-fisher interactions in the human-dominated forests of Wisconsin to conserved forests in Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota. I used boosted regression trees to develop species distribution models and confirmed that landscape heterogeneity had a positive effect on marten-fisher co-occurrence in the conserved landscape (Manlick et al. Accepted,). However, landscape heterogeneity had insignificant and even negative effects on co-occurrence in the human-dominated landscapes of Wisconsin (Fig. 1). This indicates that the relationship between landscape heterogeneity and coexistence are decoupled by human disturbances. Further, we found that snow depth mediated marten and fisher distributions, meaning climate change will likely exacerbate the negative impacts of land-use change on competitive interactions. Collectively, this work confirmed that land-use change is likely limiting marten recovery via enhanced competition.

Figure 1. The relationship between landscape heterogeneity and probability of marten-fisher co-occurrence in the Chequamegon National Forest (top, A-C) and Voyageurs National Park (bottom, D-F) at 1, 5, and 10 km2 scales. Solid lines denote significant relationships, dashed lines denote non-significant relationships, and shaded ribbons illustrate 95% confidence intervals. These results illustrate the contrasting effects of landscape heterogeneity on carnivore co-occurrence in natural and human-dominated systems.

This work was supported by: